Art Spiegelman interview

November 10, 2011 | Interviews

Twenty-five years of answering the same questions over and over again could drive a person to madness.

Or, in the case of Art Spiegelman, inspire greatness.

In the quarter century since Spiegelman’s groundbreaking — and Pulitzer Prize-winning — graphic novel, Maus, debuted, he’s faced a deluge of queries from hundreds, if not thousands, of journalists, academics, students and fans. Everyone wants to know what inspired him to portray Jews as mice, Nazis as cats and recount, as a comic book, his father’s extraordinary tale of surviving the Holocaust.

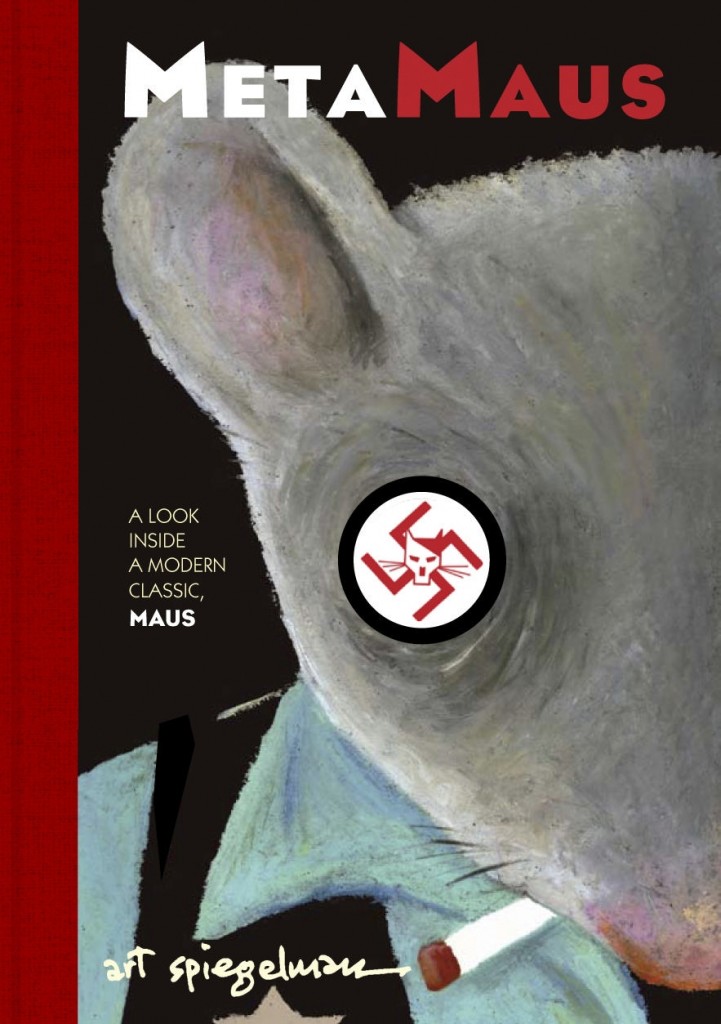

So to mark Maus’ silver anniversary, Spiegelman put all his answers — and an incredible wealth of art and other material, including a jam-packed DVD-ROM — into MetaMaus, a new book that offers an inside look at the book that first bridged comic books and literature.

“I figured I’d just turn around and try to stare my beast down,” Spiegelman told the Star in a telephone interview from his New York City studio, as he admitted the four years he spent working on MetaMaus have helped hone his answers to well-rehearsed perfection.

‘If you get asked the same things over and over and over again about any given book, ultimately your name, rank and serial number remain the same from interview to interview and bit by bit you kind of learn to get it all down to that little smooth nugget of an answer.

“What’s interesting here is, working with (associate editor) Hillary (Chute) for such a long period of time, we’re able to really have the time to find the nooks and crannies and then re-reduce the book down to something manageable that wouldn’t be five times longer than Maus.”

The challenge, Spiegelman said, was to avoid simply having a big birthday party for Maus in book form.

“(MetaMaus is) a book that, as I worked on it, became more and more like a real book. I understand that it grew up as something that can really become deadly: an anniversary book, a book about a book — it starts feeling kind of tertiary,” he said. “And yet, by the time I was immersed in it, I had to get over the same kinds of woundings that led to the original Maus and had to relive a lot of stuff that I’d kind of managed to re-suppress and by the time it came together I felt protective of it. So it wasn’t just: ‘scurry out into the world, my little MetaMaus.'”

The new book delves deeply into the 63-year-old cartoonist’s creative process in what he hopes won’t take away from the enjoyment of the original story.

“There’s one place (in the book) where I talk about admiring the notion of a magic act that tells you how something is done and leaves the magic intact,” Spiegelman said.

“That was the goal, although it did involve allowing me to give everything I could as I kind of look at Maus again so there ultimately does become a work of ‘what does it mean to be alive, process one’s life and traumas — and even pleasures — and try to find a form.’ Well beyond the specifics of Maus, it becomes ‘what is process, what does it mean to actually take the raw stuff of one’s life and make something out of it.'”

While Maus quickly evolved to the point where it is often grouped with the likes of The Diary of Anne Frank as a seminal book about the Holocaust and is often used as a teaching text, its creator says he never intended for it to be classroom material — or to be read by children.

“I never made the book to teach anybody anything, I made Maus to engage readers in a narrative,” Spiegelman said.

“There is a kind of afterlife for Maus that I’m grateful for, but it took me a while to get used to it. I used to be horrified when I heard that it was being taught in schools — even as young as in middle schools. It took me a while to come around and understand that a) comics are a very democratic medium; b) there are stupid adults and smart kids so it’s not for me to decide who ought to read it.”

Maus may be easy for sophisticated modern fans of graphic novels to read and enjoy, but Spiegelman said the process of getting it published was no small feat.

“It’s all kind of amazing how much moves along in a mere quarter of a century,” he said. “At the time that Maus was done, there was just no context for this. There wasn’t a world that was clamouring for anything like this — quite the contrary, say those rejection slips that find their way into a spread of MetaMaus. Despite the fact that the phrase graphic novel was invented, it didn’t exist as a category.

“Now, when I talk to the younger folks, they can barely remember a time when there was anything pejorative about being a comic artist. If I went into a bar to pick up a girl back in my twenties, I wouldn’t say I was a comic book artist, I’d say I was a plumber — it would have more sex appeal. Now these younger (cartoonists) are like rock stars.”

The work of these ‘rock stars’, a majority of whom claim Spiegelman as an inspiration, continues to impress him.

“They’re all mind blowing and they’re now appreciated as mind blowing,” he said.

Though none have ever earned a Pulitzer, like Spiegelman did in 1992, a special award presented to him after the completion of the second, and final, volume of Maus.

“It’s surprising to me that I won it,” he said, before quipping: “I always thought that a special Pulitzer is like winning the Special Olympics.”

One of the most succinct and best polished answers in MetaMaus follows the question of why has this incredible story never been turned into a Hollywood film.

“As I said in the book, I keep (a copy) in a glass bookcase that has the words ‘in case of economic emergency, break glass,'” Spiegelman said with a chuckle. “I’ve been blessed so far that I haven’t had to do something that I feel is a betrayal of the work.”

But perhaps the most important aspect of the new book for its creator is giving his late father, Vladek, another chance to have his story told.

“I imagine that, on some level, in my dream life, he’d be glad to have his Maus mask off and speak for himself in the transcript in the back (of the book) and in the DVD that accompanies it,” Spiegelman said. “And if he’s not, I am.”

(This article first appeared in the Toronto Star)

You must be logged in to post a comment.